A woman's place is in a safe city

Designing feminist cities through Nirbhaya Funds

Chapter 1

Introducing the Nirbhaya Fund and Government of India’s Safe City Project

What explains the recent proliferation of CCTVs on the streets of Indian cities, and where does the funding for it come from? Does such state surveillance – the monitoring of people’s behaviour or data by governments – help prevent the violence that cisgender and transgender women experience regularly in public spaces? What role does digital surveillance play in women’s own vision of safe cities? How should state funds be allocated to make this vision a reality?

More than 400, 000 crimes against women in India were recorded in 2021. In its 2013 annual budget, the Government of India announced the allocation of INR 4,357.62 crore towards the 'Nirbhaya Fund' to 'support initiatives protecting the dignity and ensuring safety of women in India.'This allocation came in the aftermath of the Nirbhaya case, involving a brutal gang-rape and murder in New Delhi in December 2012. A major focus of the Nirbhaya Fund is on 'innovative use of technology.'

One of the biggest Government of India initiatives under the Nirbhaya Fund is the 'Safe City Project' sanctioned for INR 2,919.55 crore in eight Indian cities – Delhi, Kolkata, Mumbai, Chennai, Hyderabad, Bengaluru, Ahmedabad, and Lucknow – for providing 'safety to women in public places.' The Safe City project budget accounts for 68% of the Nirbhaya Fund, making it the largest beneficiary of the Nirbhaya Fund. Technological interventions sanctioned under the project include the deployment of facial recognition-enabled CCTV cameras, the provision of a ‘video surveillance system’ in railways, and the development of a ‘panic switch-based safety device’ for cars and buses for aiding women’s safety.

Between 2013-2018, the Nirbhaya Fund was severely underutilised, with no state using more than 50% of the funds available to it. Based on data from 28 April 2023 available on the Nirbhaya Dashboard, we analysed that 46% of the Nirbhaya funds are allocated to surveillance and policing functions, with the remaining 35% allocated to survivor-centric assistance, 12% to legislative/judicial measures and only 5% to education/training for violence prevention. Moreover, the Nirbhaya Funds seem to utilise a conception of 'women' that doesn't explicitly include the needs and experiences of trans women. Data on the utilization of the Nirbhaya funds released in response to a question asked in the Lok Saba on 8 December 2023 also shows that most of the funds are allocated to surveillance and policing functions.

Feminists situate surveillance in a long line of patriarchal management that seeks to police women's bodies, erase trans/queer bodies, stigmatise disabled bodies, and enforce gender norms that place cultural expectations upon cisgender women to behave a certain way. This often has the effect of normalising and worsening violence, as well as limiting women’s public mobility. For instance, in 2012, Odisha police installed two CCTV cameras on its beach in Puri outside a temple 'to keep tabs on anti-social elements who troubled women visitors.' Soon, however, the cameras had to be taken down after women in the area began protesting that they felt the cameras were intruding on their privacy when they were swimming.

Moreover, when surveillance is carried out using Artificial Intelligence (AI) Facial Recognition Technologies, as is being done under the Safe City project, it can be highly inaccurate and prone to bias for dark-skinned persons. This is dangerous when used for policing as it can lead to false identifications and false arrests. For instance, in 2018 an innocent man was held for 54 days in jail due to being misidentified. The public accuracy levels released by Delhi police have been characterised as 'far too low to ensure the accurate identification of individuals.'

Given such evidence of the harms of surveillance, the massive capital investment allocated under the Safe City project for implementing surveillance infrastructure owned and operated by law enforcement raises concerns that motivated our research.

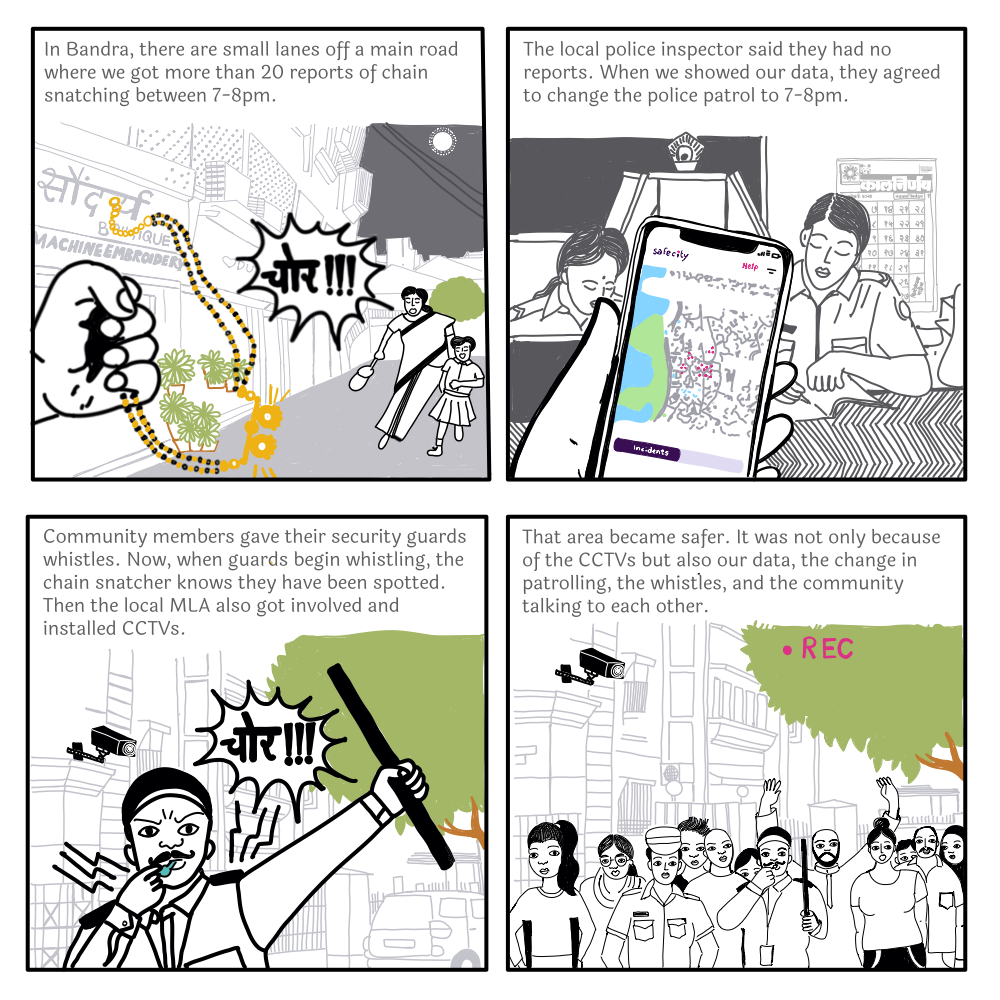

Surveillance is not always harmful. It can also be an empowering tool for marginalised communities as evidence of innocence in cases of false accusations or when police officials refuse to believe their testimonies and experiences of violence. For instance, in 2013, residents of Nalasopara, a Muslim-majority slum in Mumbai, voluntarily installed CCTV cameras in their locality to expose false arrests of Muslim slum dwellers by the police during episodes of communal violence.

The issue of surveillance for the safety of cisgender women and trans/queer communities thus depends on context: Who is surveilling? Who is being surveilled? How much control do the surveilled have over their circumstances and data? There are no easy answers, and it is important to open up informed public discussions about it.

In this essay, we focus on the cities of Mumbai and Kolkata, to explore visions of a city where cis and trans women and all queer people truly feel safe. What would a safe city look like for them? And what role does surveillance play in this vision? Based on interviews with the grassroots organisations who are providing direct services and support to survivors, our project proposes where government funds should be allocated, beyond surveillance, to turn this vision into a reality. We end with a call to action for how you can support feminist initiatives for safe cities.